Crichton, Gell-Mann Amnesia and the NFL Draft

As leaders, we have to understand that there are few experts and even fewer with knowledge of the decision-making process we endured.

What do Michael Crichton, NFL Draft grades and Murray Gell-Mann all have in common?

Crichton is an American author and television writer who has penned over 26 novels, selling more than 200 million copies worldwide. After graduating from medical school, Crichton bypassed becoming a doctor and instead used his knowledge to write science-fiction thrillers such as Jurassic Park and Twister.

He is also credited with developing the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect, named after an American physicist who won a Noble Peace Prize for his theory of elementary particles.

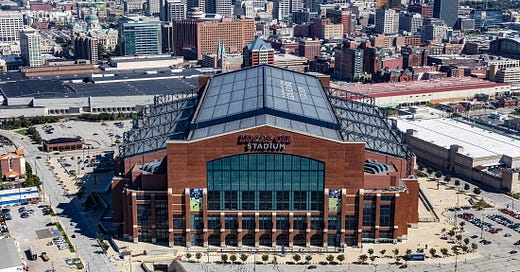

After every NFL draft, teams are graded on their selection by members of the media who have evaluated the prospects. Draft grades then typically make a fan base happy, irate or extremely sad.

The three tie together in this manner. When an NFL executive is reading a poor draft grade for his team, he can then cast doubt on the credentials of the evaluator. He then finds multiple errors in the report and becomes exasperated and upset, giving the author no credibility.

But when the same executive reads another team’s grade, good or bad, done by the same author, he believes every word, as if the evaluator somehow improved.

“I refer to it by this name because I once discussed it with Murray Gell-Mann, and by dropping a famous name, I imply greater importance to myself, and to the effect than it would otherwise have,” Crichton said.

We all fall victim to the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect at times. When we read something we have deep knowledge and an understanding of, we become critical and skeptical of the validity of the information. When we transfer to another subject outside our expertise, we believe everything written, never questioning the information.

As leaders, what we have to understand is there are few experts and even fewer with the knowledge of our decision-making process. If we let an unqualified opinion create added uncertainty, then subconsciously, we will hinder our process the next time.

Making high or low-level decisions comes with second-guessing. But if we pick and chose whose opinions we value — despite limited expertise behind them — then we can easily begin making decisions attempting to please the assessor instead of doing what we know is right.

Ask any executive if he would rather have an A today and a bad team two years from now, or a D and a good team?

We know the answer, so instead of falling victim to Amnesia, we need to ignore the noise and do what we believe is in our best interest.

Trust your area of expertise — and few others.